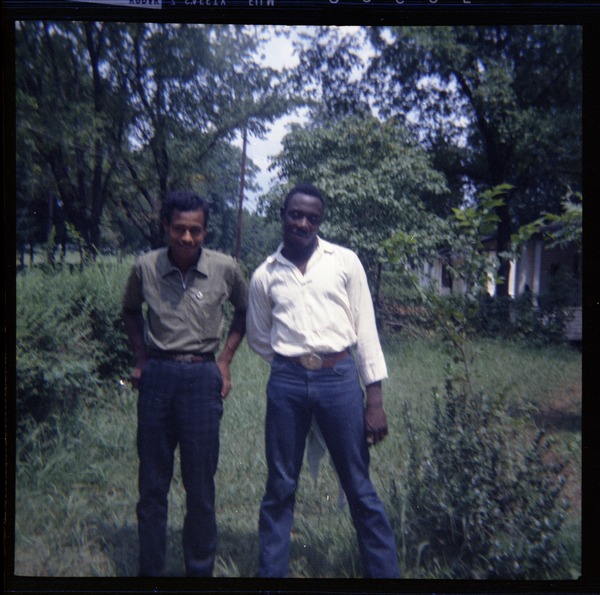

Charles T. Scales (left) and Wayne Yancey (right).

August 1, 1964

Source: Gloria Xifaras Clark Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries

“We have thought to dedicate this program

to the memory of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman,

Michael Schwerner and Wayne Yancey,

who died this summer in Mississippi.”

—Chicago Friends of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “Mississippi Report Dinner,” October 3, 1964

We are the survivors of Mississippi

but I knew one who did not come back

Not one of the murdered

the three young men, two Jewish and one Black

but the fourth who died that summer of 1964

in a car accident that may or may not have been an accident

He is the forgotten one

—Chude Allen, “Wayne Yancey,” 2014

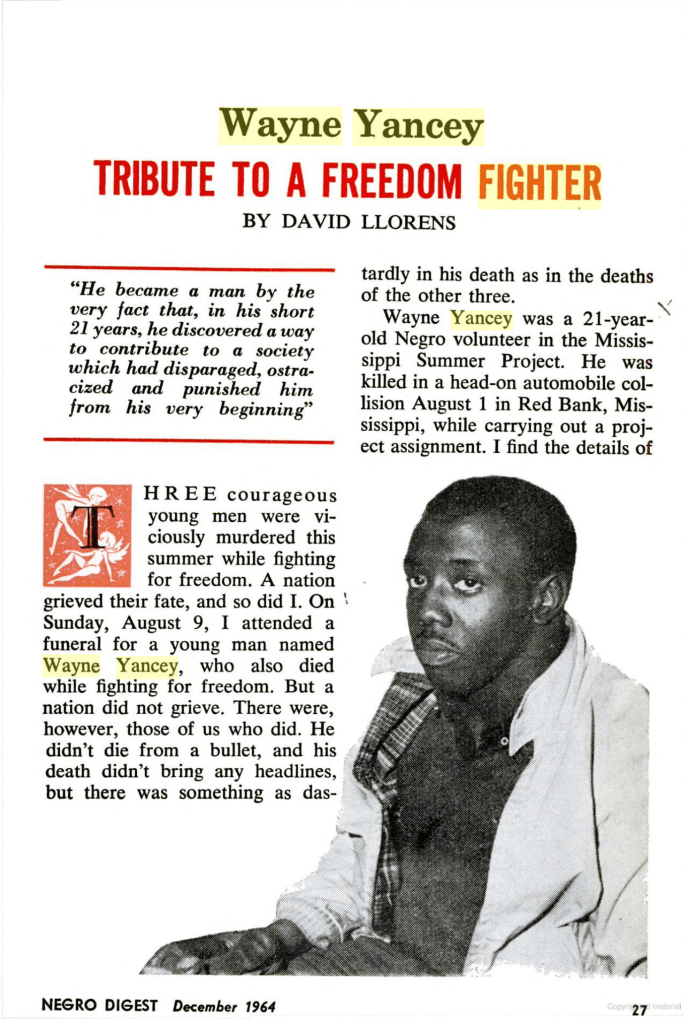

In December 1964, Freedom Summer volunteer and news editor David Llorens published “Wayne Yancey: Tribute to a Freedom Fighter” in the Negro Digest. He began with the familiar narrative that emerged out of Freedom Summer, known then as the Mississippi Summer Project: the murders of Freedom Summer volunteer Andrew Goodman of New York and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) workers James Chaney of Meridian, Mississippi and Michael Schwerner of New York. Their murders stood at the forefront of the summer, with the three men going missing after the first week of training.

Often remembered in scholarship and tributes surrounding Freedom Summer are the three. Often forgotten is Wayne Yancey.

Llorens recalled attending Yancey’s funeral on August 9, 1964. A few months later, he wrote, “But a nation did not grieve. There were, however, those of us who did. He didn’t die from a bullet, and his death didn’t bring any headlines, but there was something as dastardly in his death as in the deaths of the other three.”

—David Llorens, “Wayne Yancey: Tribute to a Freedom Fighter,” Negro Digest, December 1964.

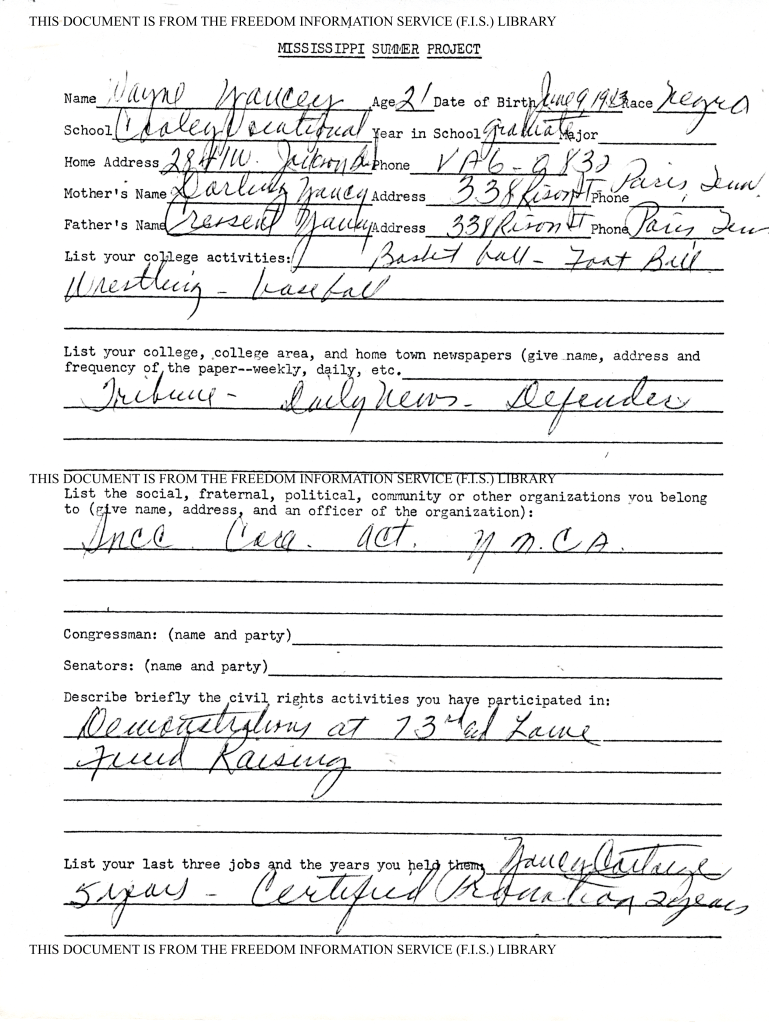

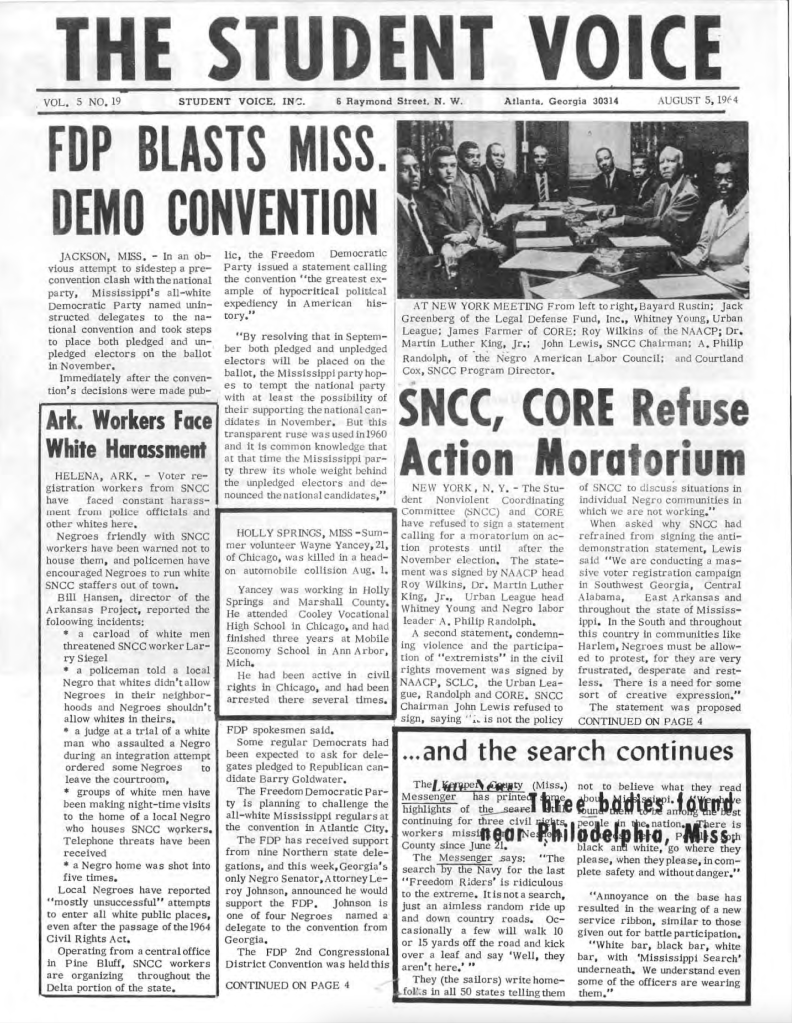

Born June 9, 1943, Wayne Yancey came of age in Paris, Tennessee and Chicago, Illinois, graduating from Cooley Vocational High School. In the midwest, Yancey worked as a welder and became active in the Movement, organizing with the city’s Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee chapter. Llorens and Yancey paths cross in activist circles with the men working with civil rights organizations in Chicago, New York City, and Atlanta before going to Mississippi that summer of 1964.

—Wayne Yancey’s Freedom Summer Application, F.I.S. Library.

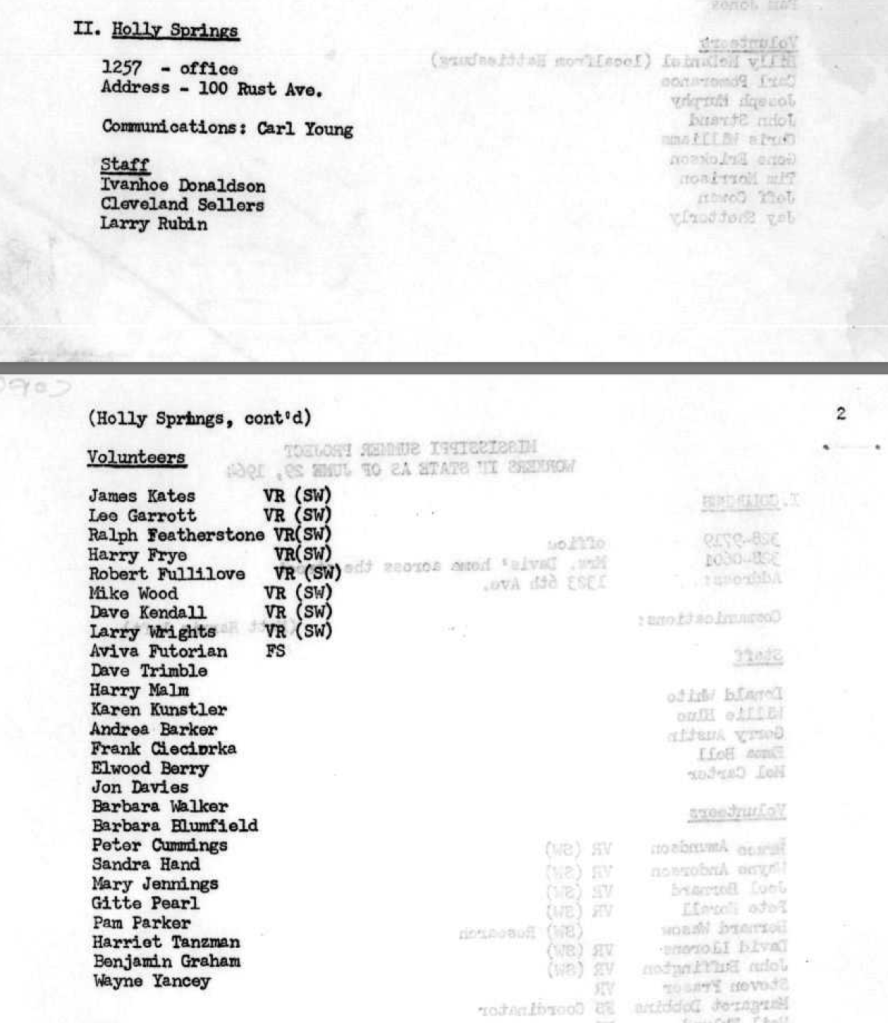

SNCC assigned Yancey to Holly Springs, a town near the Tennessee border where he grew up in a small community called Paris. He organized with roughly 25 other volunteers under the leadership of SNCC staff members Ivanhoe Donaldson, Cleveland Sellers, and Larry Rubin. Organizing across the nation, Yancey kept his hometown in mind. Llorens shared that he wanted those in Holly Springs to join him for a civil rights project in Paris. “It’s a small town and in a few weeks we can really shake it up,” Llorens recalled Yancey sharing.

—Council of Federated Organizations, “Mississippi Summer Project Workers in State as of June 29, 1964

Holly Springs volunteer Chube Allen shared the following story about Yancey. That summer when staff closed Benton County Freedom School due to bad weather. Along with another teacher, Yancey drove a group of children home who still arrived at school and lived miles away. She stated, “So that shows you he was a caring person.”

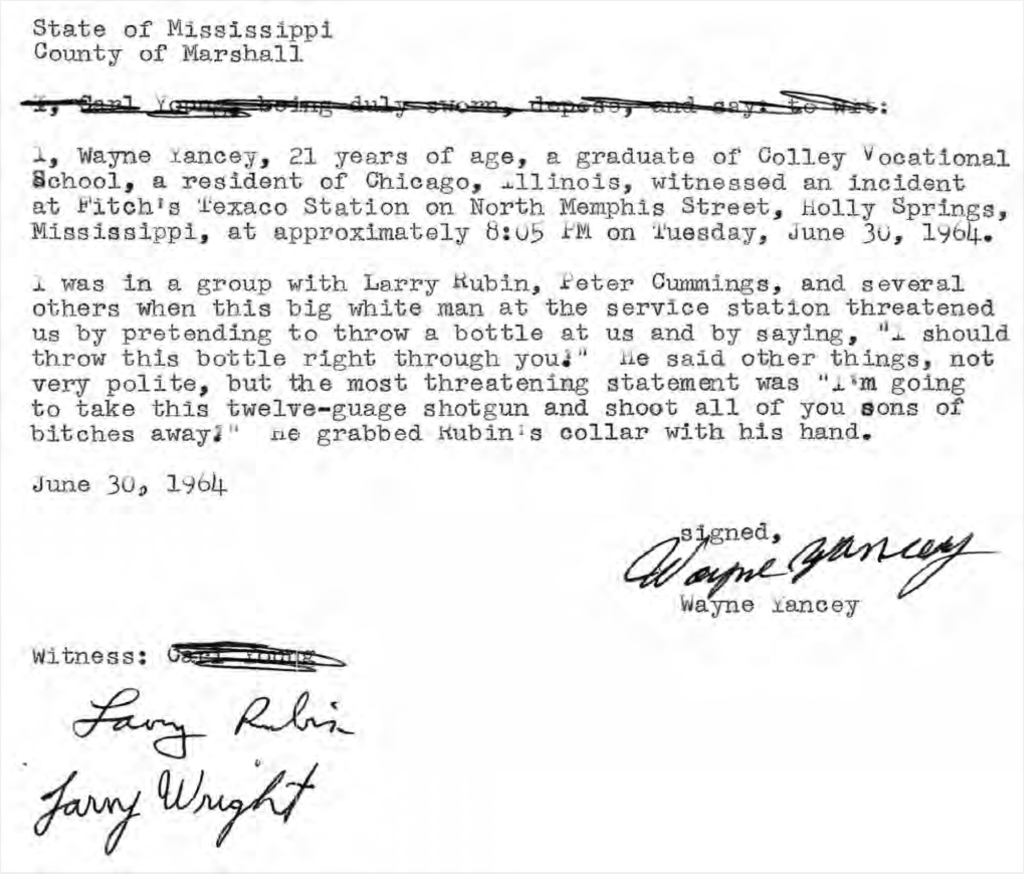

Affadavit of Wayne Yancey, June 30, 1964.

—”Wayne Yancey and Marjorie Merrill at Miss Modena’s, or Walker’s Cafe,” August 1964, Gloria Xifaras Clark Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

When two volunteers, one including Gloria Xifaras Clark, were leaving at the end of the summer, Yancey and local volunteer Charlie Scales drove them to the Memphis airport. On the way back, Yancey and Scales’ Highway 78, five miles north of Holly Springs when he hit another car head-on. According to the South Reporter, both men had severe injuries with Yancey’s being fatal.

“…and it was on the way home that the accident happened. No one, as far as I know, has ever been clear about what happened. But Wayne was killed, and the other man was the one who was driving. And when he woke up, I guess there was a gun in his face. The thing was, he was very badly injured. And this, again, to tell you about the context of the times, the hospital in Holly Springs would not admit him. It was the funeral director of the Black funeral home who drove this man in his hearse up to Tennessee to get treatment. Now, he did survive. And he was told that if he came back to Holly Springs—and remember, he’s a local man; this is where he’s from—that he would be arrested and accused of killing Wayne, because he was the one that was driving. So as I say, no one quite knew why—whether or not it was set up, what exactly happened.”

—Chude Pamela Allen, “Chude Pamela Allen: The Political is Personal,” conducted by Amanda Tewes in 2020-2021, Bancroft Library: Oral History Center (UC-Berkeley), 2022.

Project Director Cleveland Sellers learned of the accident when someone approached the group and said, “A Freedom Rider has been killed up the road in a car crash!” Sellers wrote:

“We had not seen an ambulance or emergency vehicle. We began to scout around to see what was going on. We found the badly damage car at a service station and then went to the hospital. Oddly, the police were already at the hospital.”

Holly Springs SNCC staff worker Larry Rubin agreed with Allen’s sentiments. In an oral interview, he shared, “[Yancey] from Chicago was killed in what the police called an auto accident, but which we believed and had a lot of evidence for, was a killing, that the police ran him off the road on purpose.”

“Rubin: Well, of course we don’t know for certain, but no. We believed―see, Wayne had gotten into the face of some of the deputies there. He was a very, as you know, aggressive person, and he had been involved in a few incidents. And he just wouldn’t take any crap from anybody. And we believe that the deputies ran him off the road on purpose and killed him. It was a car accident, but either rammed his car or something. It wasn’t just an accident. Might be wrong, but this is what we believed.”

—Larry Rubin, interviewed by Gloria Clark, April 28, 2001.

Rubin heard of the news when the police called the Freedom House. By the time he arrived, someone had placed Yancey on the back of a pickup truck across the street from the hospital and no doctor would examine him. When asked was he dead then, Rubin responded:

“Well, we didn’t know. There was no way of us telling. That was the whole point. And I ran into the hospital to ask a doctor to come out, and no doctor would do it because he was black, and it was a white hospital. And I went crazy. I started to scream in the hospital. And I started screaming, “Hill-Burton!” That’s the federal law, the federal funding law that if you get federal funds for hospitals, you can’t be segregated. But nobody listened, and I just went bullshit, but it came to nothing. And really we don’t know whether he was dead or not. The truth is. But I guess without a funeral home―I can’t remember exactly what happened after that. But that incident where no doctor would come out, even to examine him, to tell us was he dead or not, that was the most horrible thing that happened. I mean, after all the things that happened in the South, that incident, to me, was the most horrible.”

—Larry Rubin, interviewed by Gloria Clark, April 28, 2001.

The accident critically injured Scales. The project nurse, Kathy Dahl, attended to him, noting that he would die without medical help. Although the police took him inside the hospital, they provided no treatment. Sellers remembered that they had to ask for permission to take him to a Memphis hospital as the police wanted to press charges against Scales.

“Yet the Holly Springs hospital refused to treat him. The black funeral director saved his life, driving him to Memphis in his hearse. Then the sheriff threatened that if the injured man came back to Holly Springs, the sheriff would charge him with Wayne’s murder. This activist was a local man. He couldn’t come back to his family.”

—Chude Allen, “Why Struggle, Why Care?,” Interdisciplinary Lecture Series Letters From Mississippi and Social Justice, Western College, Miami University, September 20, 2005.

The Medical Committee for Human Rights worked with a doctor in Chicago to transport and arrange his medical care. The report read, “There was an important disposition and had to be handled rapidly because he was being inappropriately charged with manslaughter with a large bail in excess of $25,000.”

Detailing Wayne Yancey’s murder, Sellers remembered Scales’ recollection:

“Charlie maintained that as he was lying on the ground immediately following the wreck some white men walked over to him and said, “Stay still or you will get the same as your buddy.” Charlie assumed that they may have been responsible for not allowing the car to return to the appropriate lane.”

—Cleveland Sellers, “Killed: Wayne Yancey,” undated

Police arrested Sellers as he and others viewed the vehicle and retrieved items from the car. The charges: insulting an officer and resisting arrest after the police asked if it was his two friends riding in the car and made this comment: “Two bad you’all weren’t in it wit’ ’em!”

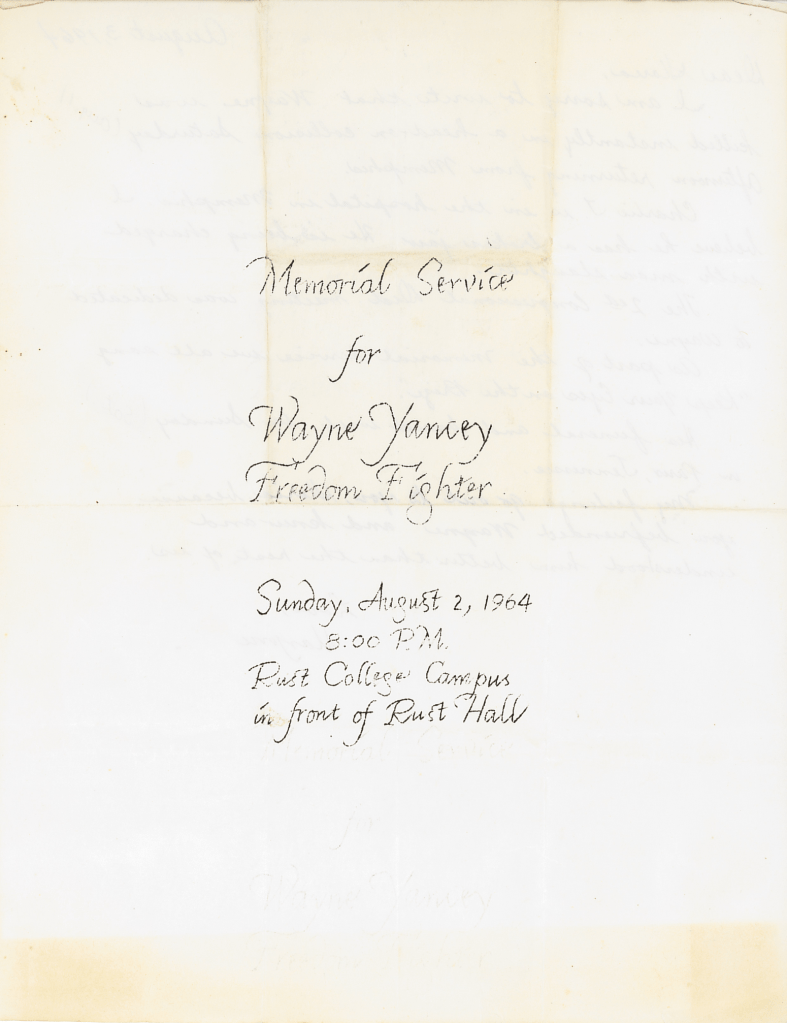

When I asked about Scales, Rubin remained unsure of what happened to the Mississippian. Sellers noted he never returned to Mississippi for safety reasons. As for Yancey, volunteers and SNCC staff gathered for a memorial service at Rust College before traveling to his homegoing service in Paris, Tennessee, on August 9th.

“When we returned to Holly Springs, we hung the cowboy hat in the living room where it remained the rest of the summer-as did Wayne’s spirit.”

—Cleveland Sellers, “Killed: Wayne Yancey,” undated

Letter from Marjorie Merrill to Gloria Xifaras Clark, August 3, 1964

“No, in his death there were no headlines, no fanfare, and very little said or known; but in his death, as in his life, there was a certain greatness that we must attempt to understand and learn from. I’m certain that in that great unknown Wayne was embraced by Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner, and somehow I could hear them saying to Wayne, “Welcome brother.”

-David Llorens, “Wayne Yancey: Tribute to a Freedom Fighter,” Negro Digest, December 1964.

Leave a reply to AliceTeague Cancel reply