I am writing my thesis, the long awaited thesis. I entitled the project “Our Children’s Children Live Forever”: The Educational Activism of the Sawyer-Flowers Family in America From 1866-1988. It is exciting, but it is a bit scary. Scary because I am writing the history of a family I have never met. Scary because it will be judged. Scary because my insecurities in my writing cause me to doubt my work. I am scared to write my thesis!

Slowly, I am gaining a new sense of confidence in my work, especially through the encouragement of my professor and peers. I just need to write and continue to edit and proofread. Since the start of classes, I write, I research, I edit, and I write even more. It is challenging some days and other days I can write four pages in two hours.

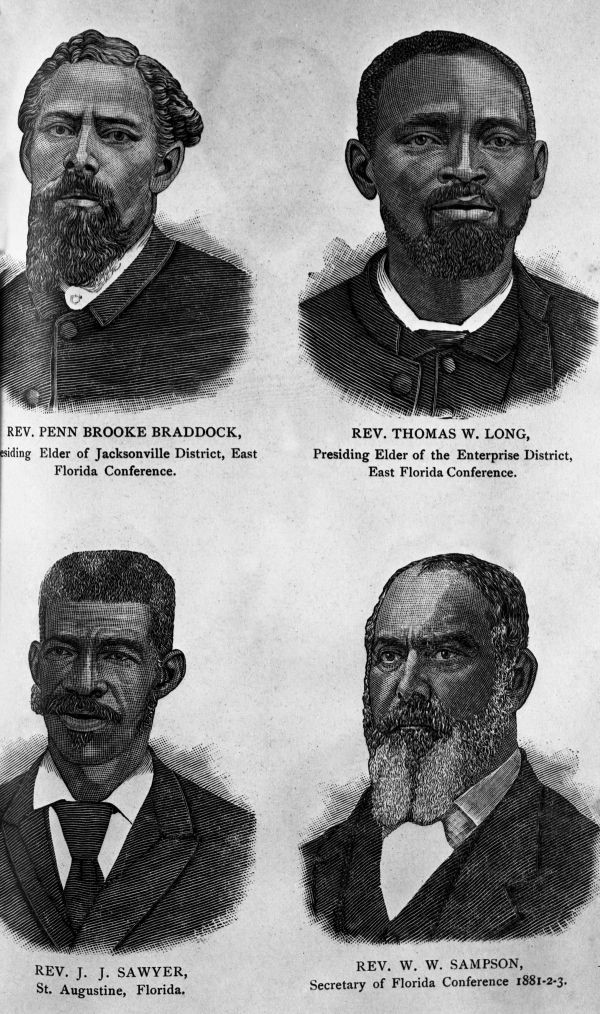

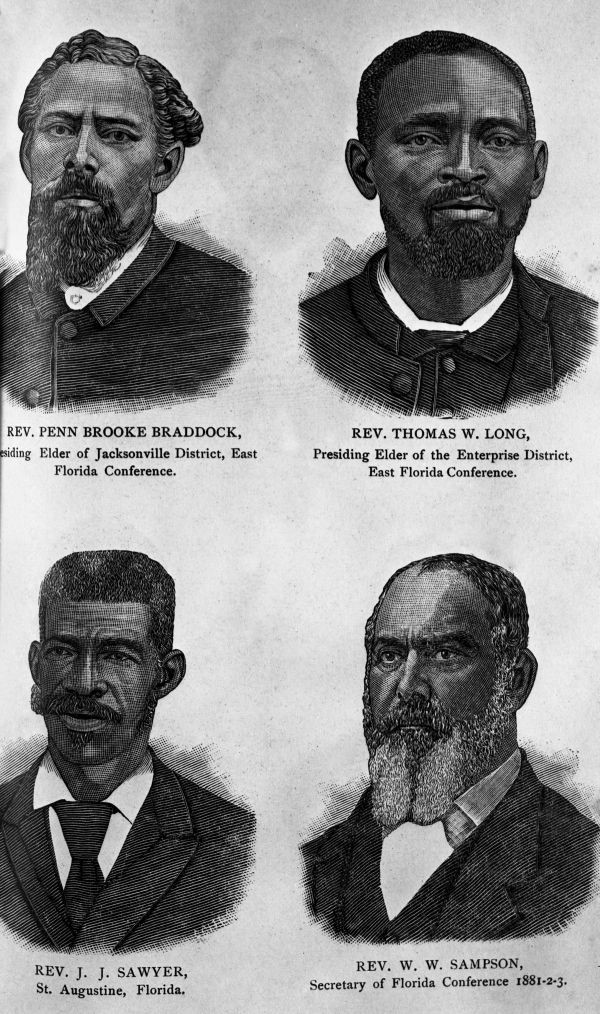

I will be posting more, I have found a significant number of primary sources on Rev. JJ Sawyer, Rachel’s grandfather, from the Discover Freedmen database. I am excited to share these documents with you.

Decided to leave you all with the standing introduction to Chapter One (“Our Children Shall Learn”: Reverend Joseph J. Sawyer and the Creation of Black School [working title]). I hope to shorten the introduction or perhaps rearrange it a bit. Any input it welcomed:)

On June 30, 1869, a 30-year old Joseph “JJ” Sawyer filled out his monthly teacher’s report for his local Freedmen’s Bureau.[1] At Zion Sabbath School, he taught six hours a day to about fifty Black children outside of Southampton County, Virginia. Sawyer served as his student’s only teacher in a one room Baptist church. Out of his fifty students, only six held basic literacy skills and only four experienced “freedom” prior to emancipation.[2] When asked to state the public’s sentiment toward “Colored Schools”, he wrote “generally favorable I believe.”[3] Five years earlier, Southern states continued to prohibit the teaching of Black children. His occupation was once illegal. Across the South, states punished Blacks, both freed and enslaved, for the educating themselves. As a result of these laws and punishments, the majority of slaves emerged from emancipation illiterate.[4] Sawyer’s students held a luxury unimaginable to him as a child. Still, their desire to receive an education outweighed their previous societal condition. This desire sparked an educational revolution throughout the South fueled by Blacks’ passion to learn and supported by Northern missionary societies and organizations. This chapter examines how Blacks utilized education as a weapon of resistance throughout this movement. Specifically, it studies the educational activism of Sawyer and his use of Northern missionary organizations, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the AME Church.

[1] The Freedmen’s Bureau set a stand monthly form to be submitted from teachers. These reports documented local teachers’ understanding of local sentiment toward Black education and data concerning enrollment, attendance, and student information. See Butchart’s Schooling the Freed People. “United States Freedmen’s Bureau, Records of the Superintendent of Education and of the Division of Education, 1865-1872” database, Family Search ((https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-909-50662-20903-59?cc=2427894 : 1 August 2016), Virginia > Roll 16, Teachers’ monthly school reports, May 1869-Aug 1869 > image 774 of 1161; citing multiple NARA microfilm publications (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1969-1978).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid

[4] J.P. Lichtenberger. “Negro Illiteracy in the United States,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 49 (1913), 177.

Until the next post,

Christina

Leave a comment