“Mississippi has long been the most perfect frame into which this republic’s black people might fit the whole picture of a cruel and unseemly white world.”

—David Llorens, Ebony, July 1969

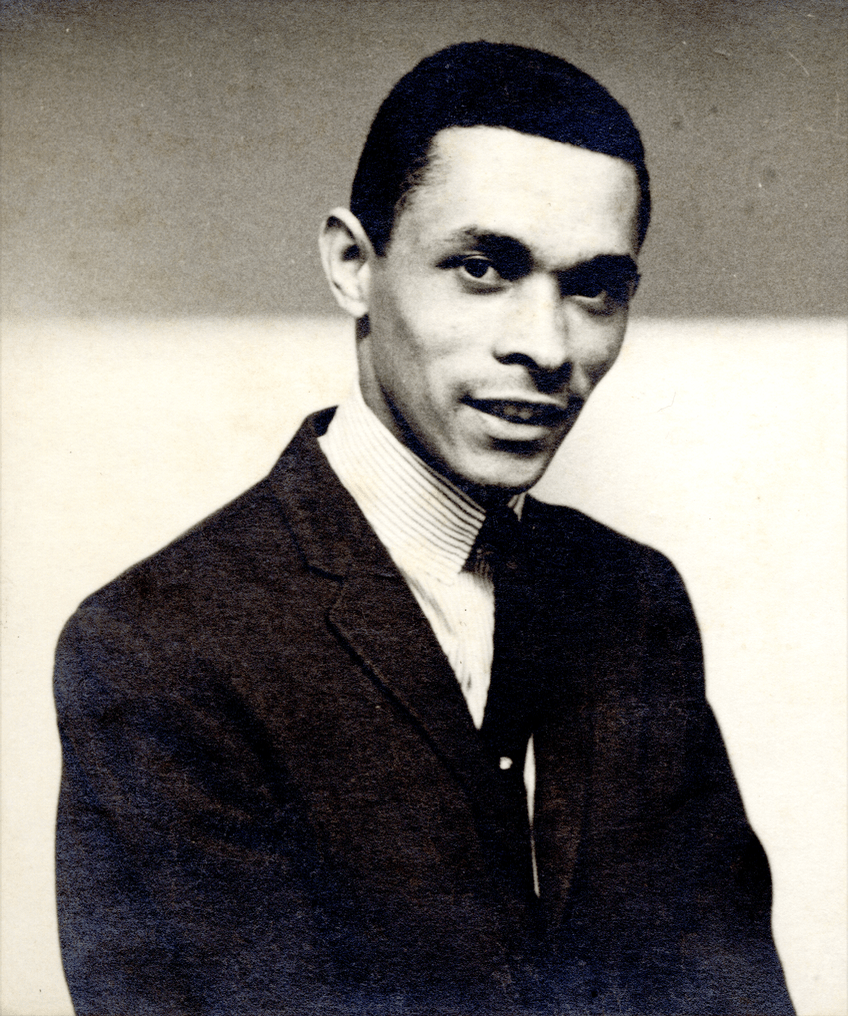

When you are in the archive, have you ever had a photo just stuck with you? I can tell you exactly the moment I came across the folder of Mississippi Summer Project applicant David Llorens of Chicago.

My research focuses on the Black volunteers who came to Mississippi that long, hot summer of 1964. With my work at the FIS Library, I began processing some of the volunteer applications. The applicants’ folders contain three to four portraits, a five-page completed application, sometimes accompanied by a two-page application from the orientation session, as well as a parental consent letter or a letter addressed to Bob Moses or the Council of Federated Organizations’ statewide headquarters in Jackson.

David Llorens was one of more than/less than 10 percent of Black applicants, and he was among the few with a full application folder. Llorens’ image was not an ordinary portrait in comparison to the others. It was much larger with a wider aspect [if that is the right terminology], and he had posed with a smile on his face.

Image of David Llorens, undated (c. 1960s), Freedom Information Service Library

Beyond his race, Llorens stood out because of his age. Unlike the majority of volunteers who were white, northern college-aged students, the Chicagoan was 24 years old, born October 12, 1939. He had previously served in the United States Air Force as an accounting clerk. At the time of his application in 1964, he was an office manager for a local baking company. When asked about his previous civil rights activities, Llorens wrote “school boycott-Chicago, Raywer Campaign against Cong. Dawson, attended SNCC conference in Atlanta in March.” He also added in parentheses, “(I’ve participated through writing for CAF [Chicago Area Friends of SNCC], picketing, leapleting, etc.”

Llorens wrote he had never been arrested, but listed the contacts of those who “could be helpful in securing your release from jail.” Out of the four names he listed, two were editors—Chuck Stone of the Chicago Defender and Hoyt W. Fuller of the Negro Digest. Llorens’ list of those to contact in the event of arrest or harassment included comedian and activist Dick Gregory.

His application began to make more sense on page 3 when he noted his freelance work as a writer for the Negro Digest and the Chicago Area Friends of SNCC. He also included an article he recently published as part of his application. Such a writing sample also supported his preference to work in communications that summer.

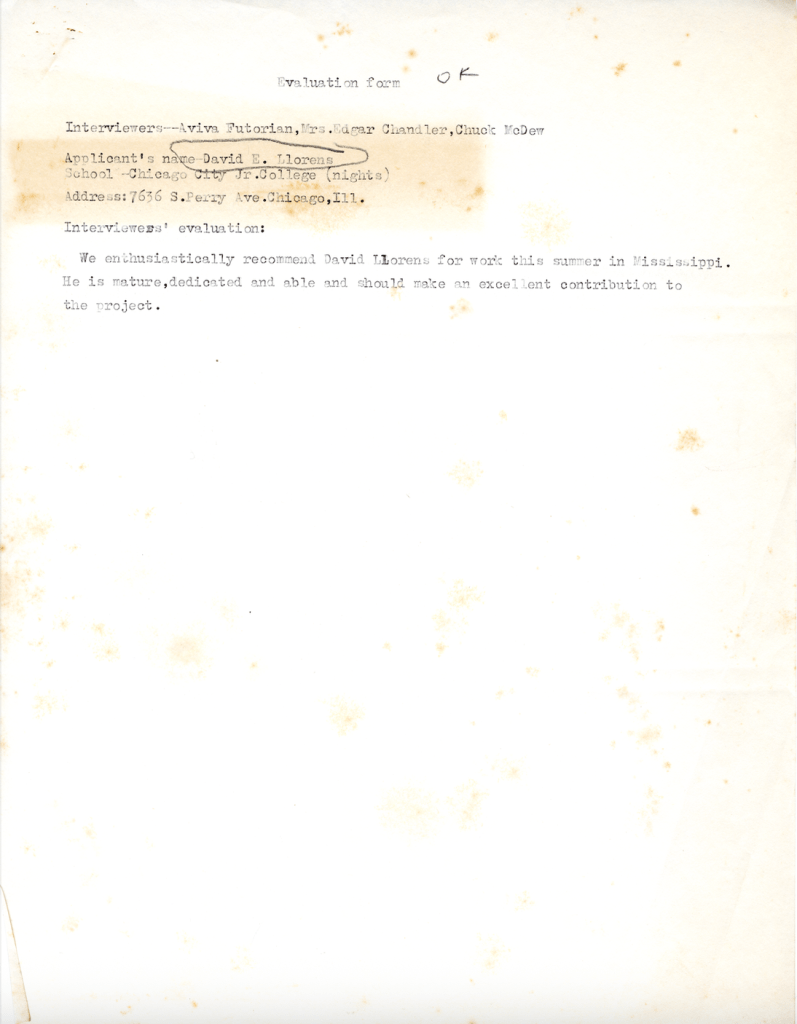

Aviva Futorian, Mrs. Edgar Chandler, and Chuck McDew interviewed LLorens for the Mississippi Summer Project. They wrote, “We enthusiastically recommend David Llorens for work this summer in Mississippi. He is mature, dedicated and able and should make an excellent contribution to the project.”

David Llorens’ Evaluation Form, FIS Library

Llorens explained his motivation in joining the Mississippi Movement in a 1968 oral history with John Britton, the staff association for the Civil Rights Documentation Project.

“I would say that I had been fairly active in Chicago for approximately seven or eight months prior to going to Mississippi which in fact, had much to do with enforcing my volunteering to go to Mississippi. Because, in fact I became very, very frustrated because I was working an eight hour job and then devoting anywhere from four to eight hours, five evenings a week or so to the movement and I was usually kind of sleepy on my job. And had decided that I really want to work full-time somehow in the movement, that I did not want that to be a part-time thing that I did and that had something to do with the decision to go to Mississippi.”

—David Llorens, interview by John Britton, 1968.

He arrived in Columbus after attending the orientation week in Oxford, Ohio. Four years later, Britton asked him about the local community’s reaction to the Mississippi Summer Project. Llorens responded:

“…and so they looked upon you as something unreal especially at a distance, they did. And it was all reflected for me by a little boy. Children can put things sometimes in their own way that gives us perspective. He walked up to us, a group of us in Columbus, and the boy was about seven years old or so, and he said, yall not Freedom Riders, y’all just plain people. And that will forever remain with me, that little boy and his words, because it was the way I wanted to think of myself…”

—David Llorens, interview by John Britton, 1968.

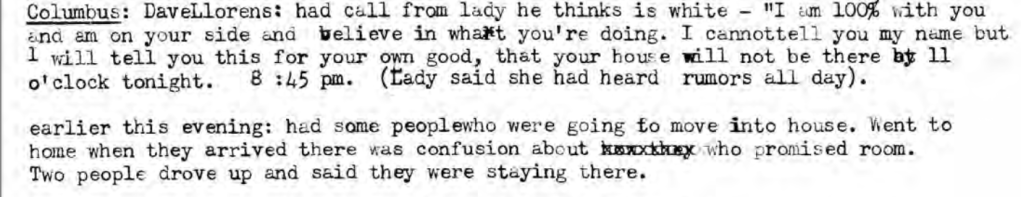

The Council of Federated Organizations [COFO], which organized the Mississippi Summer Project, sent Llorens to West Point and Columbus, Mississippi, tasked with working with voter registration and communications. On a tentative assignment list, organizers had him placed in Southwest Mississippi. Llorens gave a brief history of West Point, a city with no Freedom Riders or voter registration office. He shared, “There was no one coming through there talking about freedom, you know, for black people in this century, from what I could gather, until we went in that summer…so it was kind of virgin ground.”

Llorens identified John Buffington as the local SNCC leader, the project director of Clay County. Born in Bedford, Georgia, Buffington first came to West Point with Ralph Featherstone years prior. In his oral history, Llorens also uplifted the local people within the community, specifically a young man named Bell. Together, they attempted to integrate libraries, attempted to vote, and raise bail money for those arrested—”Because three or four of us went out that night and those poor folks just came through with their dimes and quarters and fifty cents.”

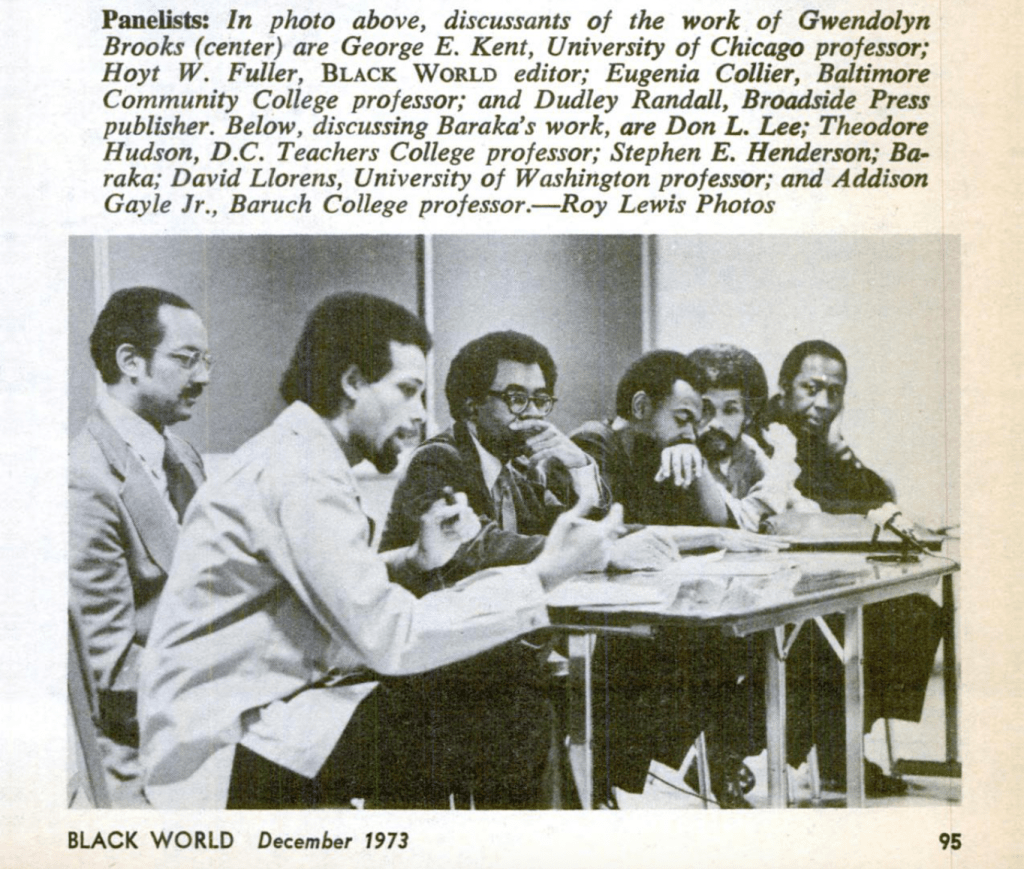

Llorens left Mississippi at the end of that summer, returning to Chicago by fall. Beyond the interview, he briefly discussed his organizing efforts in Mississippi for an article in Ebony, where he served as assistant and associate director from 1967 to 1969. Years prior, he wrote for the Negro Digest (Black World), where he worked as assistant director in 1965 and played a role in the publication of Nikki Giovanni’s first article. Giovanni wrote, “[He] either thought I showed talent or he was exceedingly kind to a young Fiskite…it made my day.” Llorens also put Haki Madhubuti on the “Black literary map,” profiling him for Ebony. His profiles also extended to other Black writers, athletes, and organizers, including Amiri Baraka, Gwendolyn Brooks, Wilson Pickett, and Jesse Jackson. He left the editorial world in 1969 to become the chair of Washington University’s Black Studies Department.

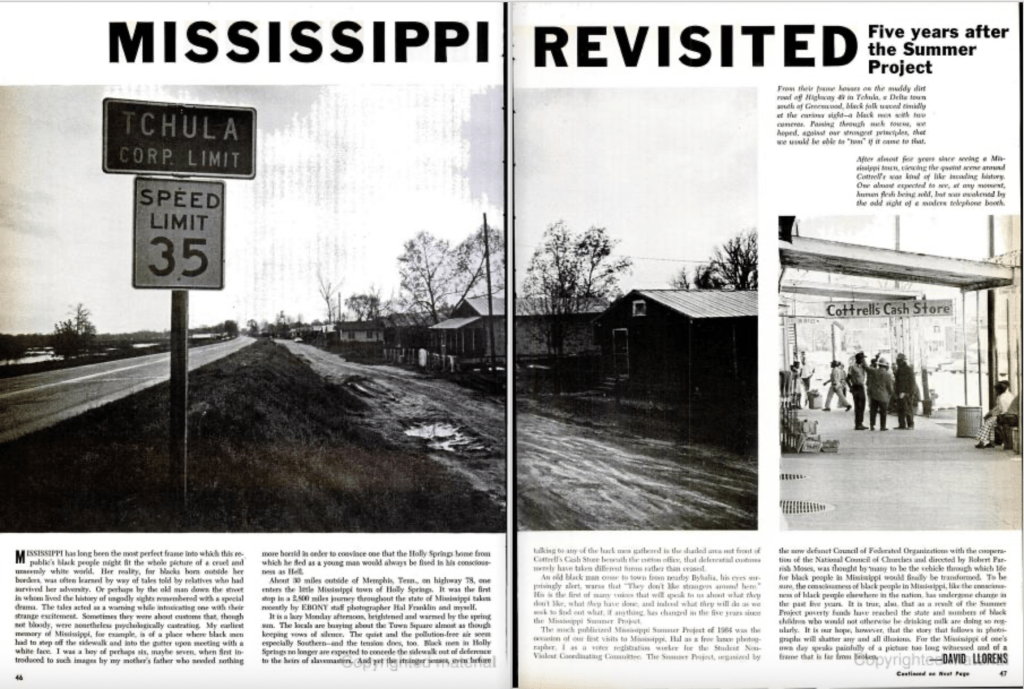

Before he left Ebony, Llorens published “Mississippi Revisited: Five Years After the Summer Project (July 1969).” He traveled back to the state along with the magazine’s staff photographer, Hal Franklin. “The much publicized Mississippi Summer Project of 1964 was the occasion of our first visits to Mississippi, Hal as a free lance photographer, I as a voter registration worker for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee.” Beyond Llorens’ oral history and this article, I was unable to locate much information about his personal experience in Mississippi.

Leave a comment